[x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 25px 0px 0px 0px; border-style: ridge; border-width: 1px 1px 1px 1px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]Author: Dr. Kristy Shine

Reviewer & Edits: Dr. John Greenwood[/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 0px 0px 0 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]

Clinical Case

69 year-old female with a history of Stage IV non-small cell lung CA s/p left pneumonectomy and tracheal/bronchial stenting (2014) presents with hemoptysis on the way home from radiation therapy. She has a recent history of esophageal stent placement 3-4 weeks ago.

On exam, she is alert & oriented with blood tinged sputum.

Vital signs are: Temp: 97.7 °F HR: 116, BP: 139/87, RR: 26, SpO2 95% on 3L NC (new oxygen requirement).

Soon after arrival, her hemoptysis worsens, she becomes increasingly dyspneic, develops altered mental status, and her blood pressure is now 84/44 mmHg. You decide to intubate/ventilate this patient.[/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]

Is there an optimal sedative for RSI in the shocked patient?

[/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_accordion][x_accordion_item title=”Answer” open=”false”]Etomidate and ketamine are often considered the most “hemodynamically neutral” sedatives for RSI.1

Ketamine’s mechanism for improving cardiac output remains controversial. It’s likely that ketamine increases cardiac output through indirect mechanisms such as potentiation of catecholamines rather than a direct effect.

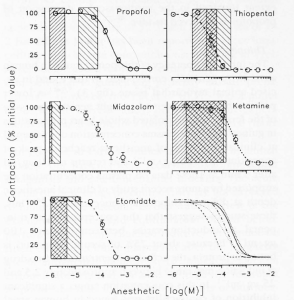

In fact, all the drugs used in RSI are myocardial depressants!!2

“How much” may be an even more important consideration than “what” to use – The dose of your anesthetic should be inversely proportional to your degree of shock.

Pearl: Of all the options for RSI – Ketamine appears to cause the lowest degree of myocardial depression with indirect mechanisms of hemodynamic support.

Due to concerns for hypotension in this case, ketamine was chosen for RSI. It’s important to provide aggressive resuscitation prior intubation, which usually means starting pressors or at least have them ready to go.[/x_accordion_item][/x_accordion][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]

OK the patient is intubated, now what vent settings do you use?

[/x_text][x_accordion][x_accordion_item title=”Answer” open=”false”]Pearl: Strongly consider using lung-protective ventilation strategies in patient with acute respiratory failure in the emergency department3

Most patients in the ED should be placed on assist-control (AC) mode, which is usually a volume cycled or (tidal) volume controlled mode of mechanical ventilation after intubation.

Ventilation (PaCO2) settings – Tidal volume (Vt) and respiratory rate (RR). For most patient, choose Vt 6-8 cc/kg (ideal body weight) In this patient with only one lung, target 6 cc/kg initially then reduce the TV if needed (we chose 260 cc). Consider the minute ventilation the patient required before intubation as well as the cause of respiratory failure when choosing a starting point.

Oxygenation (PaO2) settings – FiO2 and PEEP. Initially start your patient on 100% FiO2 and wean down to a goal of < 60%. In patient’s requiring single lung ventilation, it’s likely they will require higher FiO2‘s. PEEP is positive end expiratory pressure, which helps to keep alveoli open during the respiratory cycle. For PEEP, start at 5 cm H2O.

*check an ABG 30 minutes after intubation to reassess ventilation and oxygenation settings. If you have a good pulse-ox waveform, target an SpO2 of 92-94%.[/x_accordion_item][/x_accordion][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]

How often do we prescribe lung protective ventilation strategies in the ED?

[/x_text][x_accordion][x_accordion_item title=”Answer” open=”false”]Terrible!! or… We can do better!!

Pearl

- In a recent study of a single emergency department, approximately 27% of septic patients who were intubated received a lung protective ventilation strategy.4

- A follow-up study found similar findings – that only 56% of all comers and only 47% of patients with actual ARDS received lung protective ventilation.5

[/x_accordion_item][/x_accordion][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]

What are the common causes of respiratory distress in the intubated patient?

[/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_accordion][x_accordion_item title=”Answer” open=”false”]Pearl: The “DOPES” pneumonic can be useful for troubleshooting respiratory distress in ventillated patients

- D – dislodged ET tube (still at the teeth where intended? CXR confirmation?)

- O – obstruction (muscous plug, obstructive physiology)

- P – pneumothorax

- E – equipment (tubes ok, vent alarming etc)

- S – stacking of breaths (consider quick vent disconnect!)

[/x_accordion_item][/x_accordion][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section][x_section bg_color=”#f4f4f4″ style=”margin: 0px 0px 0px 0px; padding: 0px0 0px 0 0px; border-style: solid; border-width: 1px 1px 1px 1px; border-color: #a0a0a0; “][x_row inner_container=”true” marginless_columns=”false” bg_color=”” style=”margin: 0px auto 0px auto; padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_column bg_color=”” type=”1/1″ style=”padding: 0px 0px 0px 0px; “][x_text]References & Suggested Reading

- Stollings JL et al. Rapid sequence intubation: a review of the process and considerations when choosing medications. Annals of pharmacoptherapy. 2014; 48 (1): 62-76

- Gelissen HP, Epema AH, Henning RH, Krijnen HJ, Hennis PJ, Den hertog A. Inotropic effects of propofol, thiopental, midazolam, etomidate, and ketamine on isolated human atrial muscle. Anesthesiology. 1996;84(2):397-403.

- Wright BJ. Lung-protective ventilation strategies and adjunctive treatments for the emergency medicine patient with acute respiratory failure. Emerg Med Clin North Am. 2014;32(4):871-87.

- Fuller BM et al. Mechanical ventillation and acute lung injury in emergency department patient with severe sepsis and septic shock: an observational study. Academic Emergency Medicine. 2013 20(7):659-669

- Fuller BM, Mohr NM, Miller CN, et al. Mechanical Ventilation and ARDS in the ED: A Multicenter, Observational, Prospective, Cross-sectional Study. Chest. 2015;148(2):365-74.

[/x_text][/x_column][/x_row][/x_section]